Medieval Mead

Alcohol in Medieval Europe

Making Spiced Mead/Metheglin

We’re going back to the Medieval Europe to learn all about alcohol and make mead. We’ll discuss Hildegard the beer loving nun who changed brewing forever by advocating for hops, how the church turned alewives into witches, what Europeans were drinking and how they entertained themselves during these bleak times. It’s an understatement to say that medieval Europeans were serious about their alcohol! Tampering with alcoholic beverages in Scotland was a crime punishable by death! You would drink too if you watched 1/3 of Europe die of the plague. The collection of 11th and 12th century poems Carmina Burana has a quote that would put modern alcoholic writers to shame, “it is my firm intention, in a bar room to die.” Which makes even Hemingway sound cheery.

Today we’re making mead! First, we’ll need clean water. Spring water was pure in the countryside. Finding clean water in busy towns and cities posed a much larger challenge but many medieval beverages were first boiled to kill bacteria. Simple mead only requires water, honey and yeast. I’m adding cinnamon, cloves, cardamom and pepper to make things a little more interesting but as you know from my Food in Medieval Europe video, many of these spices were prohibitively expensive. Mead brewed with spices or herbs was often called Metheglin. While popular throughout Europe in the Middle Ages, mead was also loved by Vikings who credit mead for wisdom and poetry and with the ancient Greeks who called it the nectar of the gods. The term honeymoon even comes from the tradition of a bride’s father gifting the new couple a month’s supply of mead. Medieval mead did not ferment as long as modern mead so it was likely sweeter with less alcohol. Mead made from raw honey contains live yeast, as well as additional yeast from raisins, fruit, flowers, herbs or other flavoring ingredients that would help ferment the honey into alcohol. Without stainless steel, thermometers, basic sanitation, commercial yeast, precise recipes & measurements , medieval beverages were anything but consistent. Even from the same producer, you were likely to get very different products over time. Yeast could be taken from past brews called barm (from the top) or lees(left at the bottom). Many brewers used a special stirring stick which had yeast strains within.

The flavor is somewhat sweet, with a little bit of spice. The photo is obviously glass so you can see the color but seeing what was in your cup was a medieval rarity. Glass was very rare and expensive Actually with some of the ale descriptions I’ve read about, maybe it was best not to see the murky brew. And often at room temperature. Wooden, earthenware or pewter tankards were standard for drinkware. little wooden bowls called mazers were common for everyday drinking. Gold, silver or glass goblets were really only seen at royal feasts. Even at the finest table, drinking directly out of the jug or pitcher was not uncommon. These were also times when etiquette dictated that you could throw bones on the floor after eating the meat so who’s to judge.

The everyday drink for many Europeans was ale, and later beer, especially in Western Europe. In towns and cities, Taverns generally sold wine. Inns provided lodging, food and drink to travelers but the real party was at the ale house. Looking for some cheap ale, snacks, & excellent people watching? The ale house is the place for you. Women cornered the market on brewing ale. These alewives or brewsters would alert the town that it was ready for drinking by putting up an ale stake over the door. These ale stakes were brooms, poles, flags or any item that called attention to townspeople to get in there and drink that ale! Medieval ale only had a shelf life of around 5 days before it turned sour. Standard ale contained water, a combination of barley, oats, or wheat and yeast. No hops. Some were flavored with herbs like bog mertyl, horseradish, juniper, rosemary and mint.

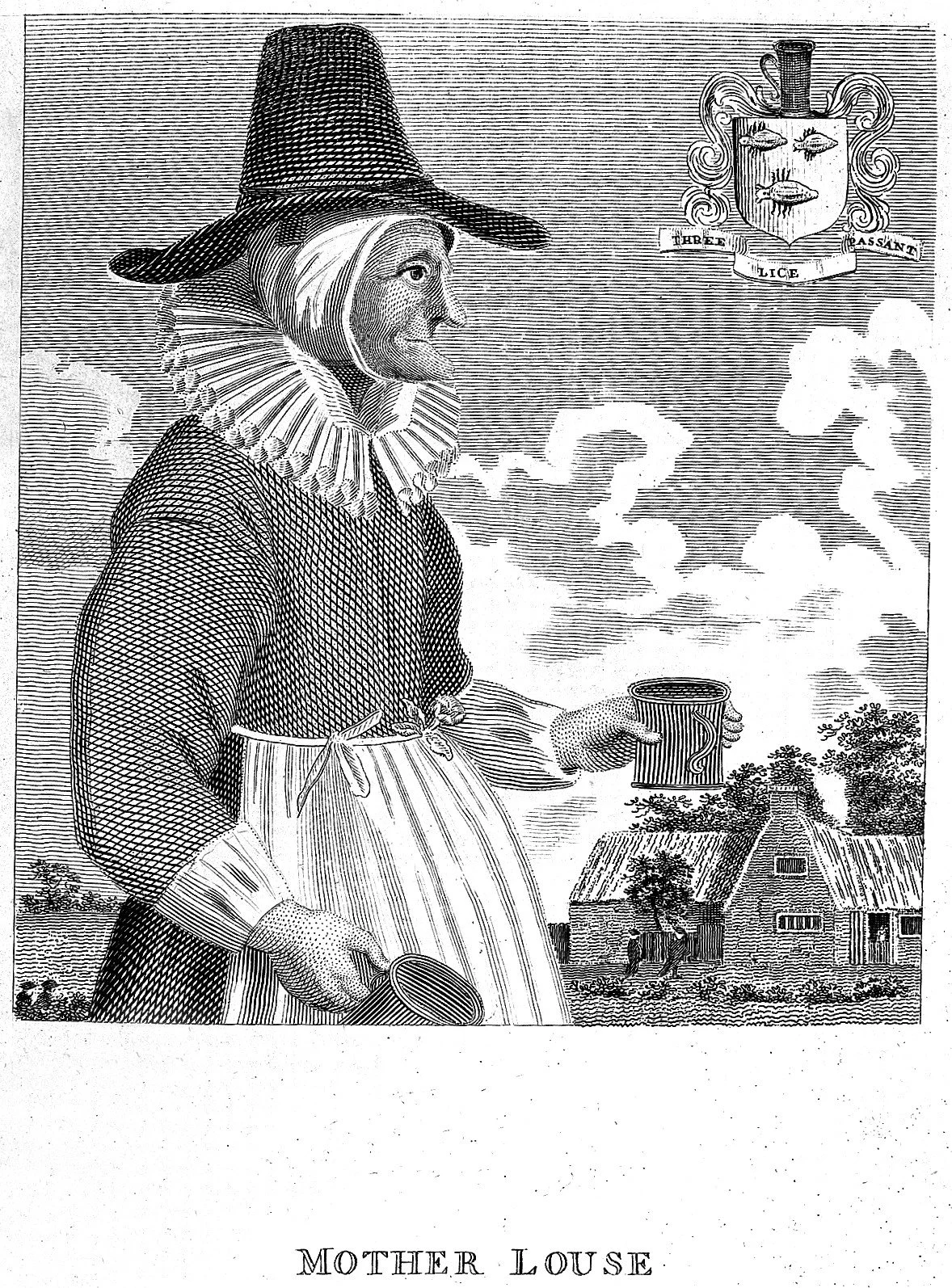

So these alewives were brewing in large cauldrons with herbs, spices, brooms over the door, oh and did i mention the pointy hats they wore to distinguish themselves at market? Surely women who sold intoxicating brews must have been witches or temptresses luring god-fearing men to away from church and into the ale house. Ugh. Perhaps larger brewers wanted to cash in on this lucrative business… and churches certainly helped by spouting sermons calling taverns “deadly rivals”, which, hello- dead giveaway that they wanted people in church instead of the ale house. Either way…the witch-hunt began and the profession of alewife was lost to history. We also get the word bridal from bride ale- an English tradition in which engaged women brewed a large batch of ale to sell to friends and family to pay for the wedding. Ale isn’t such a manly drink after all.

How did Medieval Europeans entertain themselves? Where did they drink and have fun? Of course royal and noble feasts were no doubt fun and festive. Jousting tournaments were incredibly exciting. Seasonal fairs and festivals would have been a fun way to celebrate the end of harvest -full of music, jugglers, storytelling minstrels, dancers and drinks. Traveling puppet shows were considered in the eyes of some quote “the work of the devil”…I tend to agree. The activity that sounds most dreamy to me…the noble reading party. Imagine laying in a garden being read to among the grass and flowers, mead in hand. The printing press wasn’t invented until mid 15th century so any books prior to were incredibly expensive, precious and handwritten. Many stories were recited from memory by minstrels. Drinking games and gambling in ale houses or taverns were popular pastimes. Puzzle jugs were a fun drinking game that left the participants splashed with ale.

It’s pretty common knowledge that Monks and Nuns brewed ale and beer all throughout medieval Europe. A lesser known story is that of 12th century German nun Hildegard Von Bingen and her passion for hops. Hildegard claimed to have visions sent by God. The church agreed and appointed her Mother Superior of her group of Benedictine nuns. The freedom of her own convent afforded Hildegard the time to devote to reading, writing, composing music and drinking plenty of hoppy beer. She even wrote a medical encyclopedia that was influential for hundreds of years and was considered one of the first female doctors and scientists. She correctly claimed that hops inhibit spoilage, a discovery that led to beer having a much longer shelf life & changed beer forever.

Wine was consumed and produced all over the continent. Monasteries and abbeys became major wine producers which was convenient because they needed a lot for communion. Wine was often sticky, thick, sour & riddled with adulterated ingredients like pitch, resin or wax. Standard punishment for selling funky wine was being forced to drink it in front of the town and have the rest dumped on your head. Hippocras was a popular spiced wine. Europeans had been distilling since at least the 12 century and possibly earlier. The first distilled beverages of wine called aqua vitae or water of life, were used mainly in apothecaries as medicine.

Wassail, which means cheers!

Medieval Inspired Mead

Ingredients

- 1/2 gallon distilled or spring water

- 2 cups honey

- 1/4 packet of champagne yeast (I used Lalvin Brand)

- spices: 1 cinnamon stick, 3-4 cloves, 2 cardamom pods, 5-10 black peppercorns

Instructions

- Using a food safe sanitizer or boiling water, sterilize all cooking utensils, fermentation container, bubbler and any measuring tools.

- Dissolve 1/4 packet of champagne yeast in 1 ounce of distilled or spring water (90 degrees Fahrenheit)

- Heat water over medium heat until it reaches 90-100 degrees Fahrenheit. Stir in the honey until completely dissolved. Turn off the heat.

- Transfer the warm water and honey mixture into the fermentation container (I use a glass gallon jar with a plastic lid that seals around a bubbler airlock, purchased on Amazon)

- Add the spices and the dissolved yeast. Stir.

- Cover with the lid and airlock. Make sure the water in the airlock is level according to the instructions. Allow the mead to sit in a dark, undisturbed area for anywhere from 2-6 weeks. I chose to stop the first ferment at 17 days. When the airlock stops bubbling, you know the fermentation is slowing down.

- Transfer the mead to a sterilized container that is fermentation grade. I used an old, sterilized kombucha glass bottle with a plastic top. When allowing mead to age, it is possible for the bottle to burst. Many people age their mead at room temperature for weeks up to years. I personally did not age my mead. I put my mead in the refrigerator after the first fermentation, which I’m sure more experienced mead makers would disagree with. I did allow it to age in the fridge for a few weeks and I believe the flavor did change a bit. I do not know the exact percentage of alcohol but I estimate somewhere in the 5-10% range. This resulted in a slightly sweet, nicely spiced mead that I would absolutely make again. If there any experienced mead makers, I would be very interested in hearing about your methods. Enjoy!

Notes on making mead/Historical Interpretation: Please use distilled or spring water. I am not an expert mead maker. I used raisins which would have added some natural yeast but in my recipe I include commercial packaged yeast. I also boiled the water, which medieval producers would have done to kill bacteria in the water. However, they would likely have cooled it before adding the honey which could potentially kill the active yeast in the honey. In my research I did learn that it is important to use non-chlorinated water and to make sure everything is completely sterilized. If you make mead, I’d love to hear your methods and tips. Thanks!

Sources & Suggested Reading:

O’Meara, Mallory (2021) Girly Drinks. I highly recommend this book! One of my absolute favorites.

Holland, Barbara (2007) The Joy of Drinking

Mortimer, Ian (2008) The Time Traveler’s Guide to Medieval England

Pelner Colman,Madeleine. (1976) Fabulous Feasts:Medieval Cookery and Ceremony.

Hammond, Peter (1993) Food & Feast in Medieval England

Image Credits:

David Loggan, CC BY 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Hildegard von Bingen. Line engraving by W. Marshall. CC BY 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

LuckyStarr, CC BY-SA 3.0 <http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/>, via Wikimedia Commons

Stadtmarketing Horb, CC BY-SA 4.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/4.0>, via Wikimedia Commons

Clinton & Charles Robertson from Del Rio, Texas & College Station, TX, USA, CC BY-SA 2.0 <https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/2.0>, via Wikimedia Commons